Fifteen years after the death of Senegal’s first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, the west coast village of Fadial threw a three-day party.

As part of the festivities poet and academic Waly Faye presented his life’s work: he has spent the last 30 years translating the former president’s poems from French so they can be read in one of Senegal’s native languages for the first time.

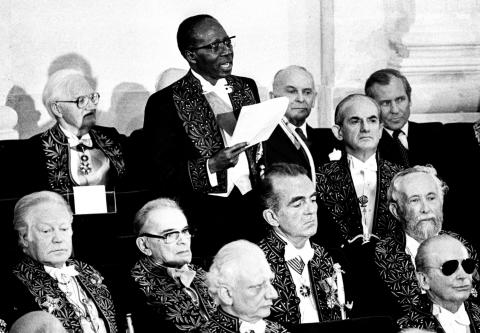

Senghor was the first of a generation of African leaders to be democratically elected in 1960 after the end of colonialism. But he was also a prominent poet and cultural theorist, and has since been hailed as one of the leading African intellectuals of the 20th century.

For Faye, my father, the fascination with the president began in the late 1970s when he started translating Senghor’s poems to help cement a sense of cultural identity and pride in the Serer people, who mostly come from the western part of the country. Though Senghor may have occasionally spoken his poems in Serer, they were only ever written down in French.

My father faced a daunting task: official figures put Senegalese adult literacy rates at 60%, and although Serer is the third most popular language spoken by roughly 15% of the country, the younger generation is losing interest in favour of Wolof or French.

Faye has long argued that students educated primarily in French or English will lose their connection with their roots. Using Senghor’s written works, Faye has pushed for the government to standardise the Serer language, which was previously written according to French phonetics but had no official written rules.

In 1978, Senghor established a committee that would decide on the language’s official spelling, using Latin script: “Until the late 1970s, the language never had an official way of writing, something that’s crucial for the legitimacy and modernisation of any language,” Faye said.

Senghor and Faye met in the late 1970s to “check over some of the translations and so Senghor could give me feedback,” Faye said. “I was lucky to get a meeting with Senghor and we got along so well. Our meeting was supposed to last for 15 minutes, but we ended up talking for nearly an hour.”

Senghor was pleased with Faye’s work and the pair stayed in touch, corresponding until the former president’s death. One of the former leader’s letters concluded: “Rest assured that my Sererness has never left me, and be certain of my loyalty to my roots.”

Faye has since translated three major collections of Senghor’s poems into Serer, which have recently been released in Senegal. He is putting the finishing touches to a four-part analysis on the president’s work in French and would like to see all of Senegal’s school textbooks translated into Serer one day.

Seydou Nourou Ndiaye, his editor and director of Editions Papyrus Afrique, a company publishing poetry and non-fiction in west African languages, warned that although local languages are experiencing a renaissance “there is virtually no money invested into the industry, and no profit to be made – despite the invaluable cultural richness”.

“During Europe’s reformation the printing press was able to make thoughts and ideas available to the working classes by publishing them in local languages, not Latin. The same needs to happen in Africa,” he said.

Back in Fadial during the party to celebrate Senghor, people sang, danced and recited poems as Faye presented his work and gave his speech entirely in Serer.

Some in the audience were overcome with emotion hearing poems read out in their own language for the first time. A woman said that she had never cried reading Senghor’s poems when in they were in French, but that she had cried all night having read them for the first time in Serer.

“I’ve been overwhelmed by the positive reaction and the magnitude of the response from [my] readers,” said Faye. “The next generation will shape Senegal’s future and they need to have a clear understanding of their roots. And Senghor’s vision.”

Source : © The Guardian